When Scream arrived in 1996, the slasher genre wasn’t just tired, it was on life support. The once-mighty franchises of the ’70s and ’80s had collapsed under the weight of diminishing returns, self-parody, and cultural irrelevance. Friday the 13th had become a punchline. A Nightmare on Elm Street had turned Freddy Krueger into a merchandising mascot. Even Halloween, the gold standard, was limping through continuity reboots that felt increasingly desperate. Horror, at least in the mainstream, had lost its edge.

Then Wes Craven – himself written off by many as a relic – picked up Kevin Williamson’s razor-sharp script and made a film that didn’t just revive the slasher movie, it interrogated it, weaponised its history, and reintroduced fear through intelligence. Scream didn’t save horror by ignoring its past; it saved it by confronting it head-on.

Nearly three decades later, with Scream 7 positioning itself as something of a culmination – “Every phone call. Every killer. Has led to this” – it’s worth looking back at how each entry didn’t merely continue a story, but actively reshaped the genre around it.

Scream (1996): The genre wakes up

The brilliance of Scream lies in its duality. It is, on its surface, a brutally effective slasher – tense, violent, and deeply unsettling. But beneath that surface is a meta-textual engine that changed how horror films could talk to their audience.

The opening scene alone rewrote the rules. Drew Barrymore, the most recognisable face in the cast, is slaughtered within minutes. The message was clear: no one is safe, and nothing you think you know applies anymore. The film’s self-awareness wasn’t smug, it was strategic. By acknowledging the clichés, Scream disarmed them, then used them more ruthlessly than ever.

Crucially, it also made horror smart again. Teenagers weren’t passive victims, they were genre-literate participants. Randy’s (Jamie Kennedy) “rules” weren’t jokes – they were structural pillars. The audience, for the first time, felt intellectually invited into the game.

And then there’s Billy Loomis (Skeet Ulrich) and Stu Macher (Matthew Lillard): two killers whose relationship crackled with an intimacy that went far beyond camaraderie. Their dynamic – obsessive, performative, emotionally charged – gave the film a queerness that was never textualised but always felt; desire, repression, performance, and violence blurred together. Horror had always been queer-coded – Scream simply stopped pretending otherwise.

Scream 2 (1997): Violence as Spectacle

If the original was about the rules of horror, Scream 2 was about the consequences of watching it.

Released just one year later, the sequel expanded the meta lens to question sequels themselves and the culture that consumes violence as entertainment. The opening murder in a packed cinema, with Ghostface hidden among a sea of costumed fans, is one of the most unsettling images in horror history. Violence doesn’t interrupt the spectacle – it is the spectacle.

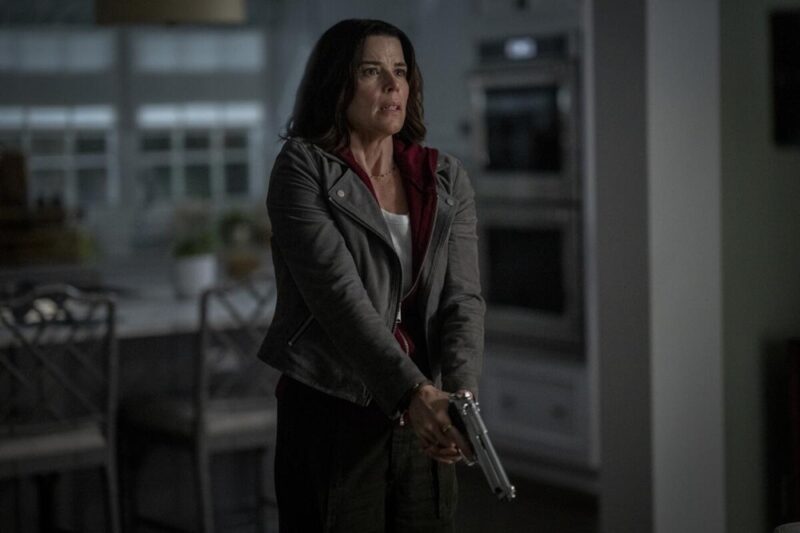

The film grapples with copycat crimes, media sensationalism, and the idea that trauma doesn’t end when the credits roll. Sidney Prescott’s (Neve Campbell) evolution from final girl to reluctant survivor grounds the increasingly operatic kills in emotional reality.

Importantly, Scream 2 also continued the franchise’s quiet queerness. The performances – especially from Timothy Olyphant’s replacement energy for Lillard – leaned into the idea that masculinity itself was unstable, theatrical, and combustible. Horror wasn’t just scary again, it was reflective.

Scream 3 (2000): Turn of the Millennium Trauma

Often dismissed as the weakest entry, Scream 3 deserves reappraisal – not least because its themes feel eerily prescient.

Set in Hollywood, the film exposes the rot beneath the dream factory, confronting abuse, exploitation, and the violence embedded in systems of power. Maureen Prescott’s reframing – from absent mother to victim of industry predation – adds a layer of institutional horror that the franchise hadn’t previously explored.

Yes, the tone is broader. Yes, the studio interference shows. But Scream 3 marked a shift away from teenage thrills toward adult reckoning. It also closed the book on the original trilogy’s obsession with legacy trauma, suggesting, at least temporarily, that survival could mean closure.

In hindsight, it’s less a misstep than a transitional text, one that struggled under the constraints of its time, but dared to point horror inward.

Scream 4 (2011): Too Smart for its Own Time

If Scream 3 was misunderstood, Scream 4 was outright ignored – and that may be its greatest irony.

Arriving in the early days of social media obsession, the film dissected fame culture, performative victimhood, and the commodification of trauma with surgical precision. Jill Roberts (Emma Roberts) wasn’t just a killer; she was an algorithmic prototype – a person willing to orchestrate mass violence for relevance, visibility, and narrative control.

The tragedy of Scream 4 is that it was right too early. Its commentary on self-branding, influencer culture, and digital narcissism would land far harder today, but in 2011, it felt abrasive, cynical, and uncomfortable in a way audiences weren’t yet prepared to embrace.

Its failure to relaunch the franchise wasn’t due to lack of insight, but excess of it. In retrospect, it may be the most forward-thinking entry of them all.

Scream (2022): Legacy as a Weapon

When Scream returned after Craven’s death, the question wasn’t whether it could continue – but whether it should.

The answer lay in its razor-focused critique of “legacy requels.” This fifth entry didn’t just feature legacy characters, it probed the entitlement of fandom itself. Its killers weren’t motivated by revenge or trauma, but by expectation, a belief that stories owed them validation.

In doing so, Scream once again dragged horror forward, calling out toxic nostalgia while still honouring its roots. The film reframed legacy characters not as a sacred species, but as survivors whose endurance was itself radical.

The queerness, too, became more explicit, not as subtext, but as texture. Identity, chosen family, and generational difference took centre stage. Horror was no longer just surviving the knife – it was surviving the discourse.

Scream VI (2023): Urban Panic and Mythology

Scream VI widened the canvas, taking Ghostface to New York and embracing scale without sacrificing intimacy. The film leaned into franchise mythology, treating Ghostface not as a singular identity but as a viral concept, one that could be inherited, replicated, and distorted.

The violence felt angrier, more physical, more relentless. In a post-pandemic, post-truth world, Scream VI captured the claustrophobia of modern fear: nowhere is safe, everyone is watching, and anonymity is a weapon.

The film suggested that Ghostface had transcended motive. The mask itself had become the monster.

Scream 7 (2026): The Ultimate Evolution

The implication with Scream 7‘s current taglines and trailers seems clear: this isn’t just another sequel. It’s a reckoning.

If the franchise has always evolved alongside the genre, then Scream 7 faces a unique challenge. Horror is no longer dying. It’s thriving – prestige-laden, critically respected, and culturally dominant. The question now isn’t how to revive horror, but how to examine its success.

Expect a film obsessed with legacy, consequence, and accumulation. A world where Ghostface isn’t just a figure, but a history. Where survival itself comes with moral weight. Where the line between audience, accomplice, and victim has completely eroded. And perhaps, finally, a film willing to say what Scream has always known: that horror doesn’t exist in isolation. It feeds on us – our obsessions, our identities, our desire to be seen.

Every phone call has led to this because Scream has never been about the killer. It’s been about the conversation. And the line is still ringing.

Scream 7 is scheduled for release in Australian theatres on February 26th, 2026, before opening in the United States on February 27th.