When Valentine hit American theaters in February 2001, it arrived at a strange and unforgiving moment for horror. The post-Scream boom had peaked, critics were exhausted by the meta-wave, and studios were scrambling to find the next box-office darling. Into this atmosphere entered a stylish, glossy, almost defiantly straightforward slasher film – one that critics dismissed, audiences overlooked, and time, for a while, forgot.

Yet 25 years later, Valentine has quietly transformed into something else: a cult gem, an early-2000s relic that has aged far better than many of its louder peers, and a film whose themes about gender, harassment, and the everyday dangers women navigate feel startlingly modern. What was once labeled “formulaic” now reads like something far more intentional: a slasher film that was ahead of the curve in its portrayal of women and the social dynamics that threaten them.

Part of Valentine’s enduring charm lies in its aesthetic confidence. Rather than chasing the self-referential energy that defined the late ’90s, the film revives the sleek, operatic mood of early giallo and late ’90s noir. It embraces sensuality and style – crimson hues, candlelit sequences, masquerade masks, and yes, a killer wearing a disturbingly blank cherub face; it’s a Valentine’s Day horror film that looks and feels like Valentine’s Day.

Upon rewatch, the most surprising quality of the film is how firmly it centers the lived experiences of its female characters – not merely as victims, but as people navigating social expectations, pressures, and dangers. Long before conversations around “toxic masculinity,” “male entitlement,” and “coercive behavior” reached the mainstream, Valentine was quietly staging them as the film’s true horror. Women endure constant microaggressions at parties, gyms, and in their own homes; dates toe the line between awkward and predatory; authority figures downplay real danger with casual dismissiveness; harassment is minimized until it escalates.

None of this is sensationalized. It’s presented as everyday life – which is precisely the point. The killer may wear a mask, but Valentine points to the ways ordinary men weaponize jealousy, resentment, and entitlement long before any blood is spilled. In its own glossy, early-2000s way, the movie was telling a story about stalking culture, rejected-man rage, and the way society often gaslights women who sense danger.

In 2001, this was brushed off. In 2026, it feels prophetic.

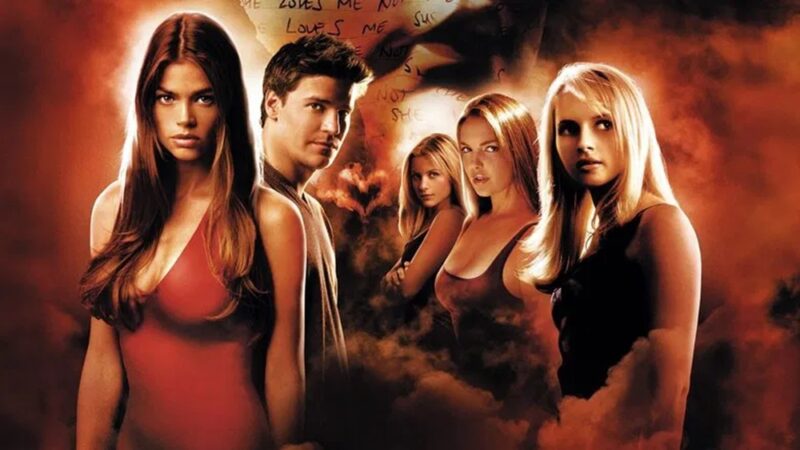

The central friend group – played by Denise Richards, Marley Shelton, Jessica Capshaw, Jessica Cauffiel, and Katherine Heigl – was dismissed at the time as “stock,” but the film actually grants these women something slashers often withheld: autonomy, career paths, complex friendships, sexual agency, and their own vulnerabilities that aren’t defined by men. They are not caricatures or punchlines. They are flawed, real, and presented with noticeable sympathy by director Jamie Blanks.

Their deaths – when they come – are not moral judgments. Valentine rejects the puritanical slasher formula that punishes women for desirability, sexuality, or independence. Instead, the film frames the killer as a product of unchecked male resentment – a narrative choice that ages remarkably well. Similarly, the film’s “abrupt” ending (as some critics mentioned) now reads as quite intentionally chilling. Valentine refuses to offer its women narrative closure because the world around them refuses it too. The final revelation is not simply unmasking a killer – it’s unmasking a culture that excuses, protects, and nurtures him. The threat isn’t just one man; it’s the systems and attitudes that allowed him to thrive.

This wasn’t laziness. It was commentary.

Revisited today, Valentine feels like a movie completely out of sync with the early 2000s – but perfectly in sync with 2026. What was once dismissed as shallow now plays as sharp. What was once perceived as glossy now reads as purposeful. What was once labeled “just another slasher” emerges as one of the era’s most quietly subversive entries. Valentine didn’t set out to redefine the genre, but it did something arguably more interesting: it offered a female-centered horror narrative that took women’s fears seriously, long before the cultural landscape caught up.

Twenty-five years later, the film’s beautiful, bloody heart finally gets the appreciation it deserved all along.