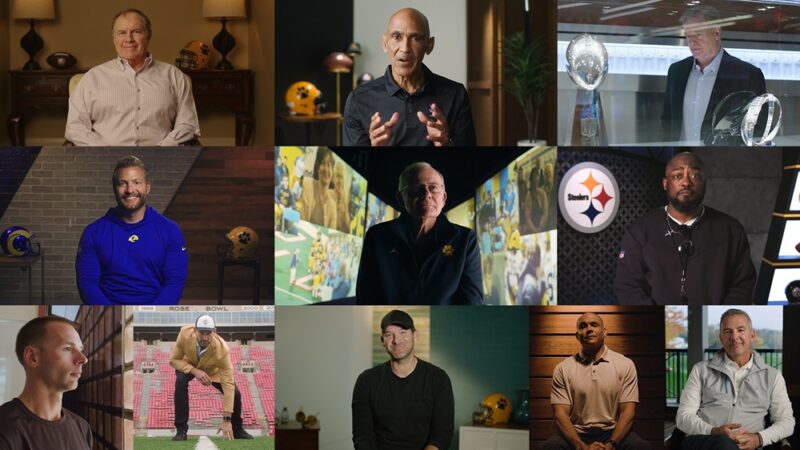

In a sport often defined by scoreboard lights, playoff runs, and Super Bowl glory, the new docuseries The Object of the Game turns its gaze back to where it all truly begins. Arriving February 4th on Prime Video (US) – timed for the most-watched week in American sport – the three-part series assembles an extraordinary lineup of football’s most influential figures, from Bill Belichick and Tony Romo to Mike Tomlin, Sean McVay, Tony Dungy, and NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell. Yet at its emotional heart is something far more intimate: the final season of legendary Cleveland high school coach Chuck “Chico” Kyle, whose four decades at Saint Ignatius shaped not just players, but people.

Directed by Matt Waldeck, the series blends verité access to Kyle’s last year on the sidelines with philosophical reflections from football royalty, interrogating what the game demands, what it gives back, and why its values endure; especially in an era increasingly defined by NIL deals and big business. It’s a film about leadership, sacrifice, brotherhood, and the foundational “why” behind football, tracing how lessons learned on a high school field echo all the way to Super Bowl Sunday.

Ahead of the series’ release, our Peter Gray spoke with Coach Kyle, former Cleveland Browns center and Hall of Famer Joe Thomas, and director Waldeck about legacy, loss, work ethic, and what football ultimately took – and gave – back.

I’ll be honest — American football isn’t something I’m completely across, so it was really nice to watch this episode and see the human side of it all. To start, I wanted to ask all of you: if you could return to one moment in your career – whether good or bad – to relive it or maybe do something differently, what would that be? Something that really put you on the path you’re on now.

Chuck “Chico” Kyle: I’ll go first. You can look at championships and all that, but I want to tell a story from when I was in eighth grade playing parish football. We were in the city championship game, and the coaching staff called me over and said, “We want you to call the defense for the entire game.” No signals from the sideline, I would be making the calls.

We ended up winning 13–0, but for years I wondered why they trusted me with that. Later, I realized they didn’t want the opposing coach reading their signals – but more importantly, that was the first time I ever felt what it was like to think like a coach rather than just a player. I was a running back – I just took the ball and hit the hole. Suddenly, I was making decisions for the whole defense. I loved it. Looking back, that was the first moment I thought, “Maybe I’d like to coach one day.” So that’s the moment I’d go back to.

Joe Thomas: For me, it would be my first college game at Wisconsin. We played West Virginia on the road, and I was a true freshman playing jumbo tight end – I basically had no idea what I was doing, just running around and blocking as hard as I could.

I’d love to go back and feel those emotions again – the nerves, the anxiety, the excitement – but this time with the perspective of knowing how my career would unfold. At the time, those feelings felt overwhelming and negative, but they were actually part of what pushed me to become the player I became.

Matt Waldeck: I actually had another story in mind, but something else just came to me. When I was 14, I didn’t want to go to St. Ignatius High School. I was defiant – I didn’t even list it as my first choice on the entrance exam, which meant they wouldn’t consider me. Then I didn’t get into my preferred school either, so I had to go back, speak to the president of St. Ignatius, and ask to be admitted.

At the time, that felt like a setback – but looking back, it completely changed my life. If that hadn’t happened, I never would have met Chico, never met Joe, and this documentary might not even exist. It’s a reminder that sometimes failures or disappointments open up a completely different, and better, path.

I really relate to that. A few years ago, I went through something that completely broke me down, and I had to rebuild myself. It made me realize how important writing and film were to me, so I understand that idea of being reshaped by adversity. I wanted to ask you both, Joe and Chuck – being completely honest – what did football take from you, and what did it give you that nothing else could?

Chuck “Chico” Kyle: It definitely took away leisure time and an “easy” life. When you’re playing, you’re balancing school, practice, workouts, and everything else. You miss out on a lot. But that sacrifice was worth it. Football teaches you that if you want a chance to be great, you have to give something up. There’s no guarantee of success, but without sacrifice, you don’t even have a chance. Practices in August in 90-degree heat aren’t fun for anyone, players or coaches, but that discipline shapes you.

Joe Thomas: Physically, football has taken a lot from me. I don’t have much cartilage left in my knees, and I had my hip replaced last year. But it’s given me far more than it’s taken. Football shaped my values: accountability, teamwork, discipline, service, and working toward something bigger than myself. It taught me how to be a good teammate, a good leader, and hopefully a good father. You can learn some of that from family, but there’s something unique about being on a team with people you’re not related to, fighting for a common goal. Winning together feels completely different – and better – than any individual success.

The documentary really highlights that football is as much about the people as it is the game. Matt, since every documentary is shaped in the edit, what was the hardest scene to include, or the hardest thing to leave out?

Matt Waldeck: The edit took about a year. The gameplay footage was fairly straightforward, but as the story evolved, it became more about the rise of NIL (Name, Image, and Likeness) in amateur sports. The challenge was balancing that conversation – explaining it clearly to the audience without vilifying it. I don’t oppose NIL; I just wanted to remind people of the soul of the game. Chico embodies that idea: that if you focus on building strong people first, the business side of sports will take care of itself. The hardest part was making sure the film wasn’t seen as “anti-NIL,” but rather as a reflection on values, identity, and character.

Chuck, you built a nationally respected program with limited resources. What was the single, non-negotiable principle you refused to compromise on?

Chuck “Chico” Kyle: Commitment. I encouraged my players to play other sports, I didn’t want them locked in the weight room year-round. But I wanted them to understand commitment and work ethic. I’d tell graduating seniors: if you want to be a doctor, go be a doctor – but have a work ethic. If you truly want it and you’re willing to work, you’ll get there. As a coach, I wanted my players to see that I worked hard for them. That mattered to me.

I sometimes feel like a grumpy old man looking at younger generations thinking work ethic isn’t what it used to be, so that’s good to hear. Joe, you played in Cleveland during some tough years. How did you stay elite when the team wasn’t winning?

Joe Thomas: I was lucky to be coached by people from the Belichick/Parcells tree – Romeo Cornell and Eric Mangini – who drilled into us: “Do your job.” I didn’t focus on the scoreboard. I focused on being the best version of myself for my teammates. I played out of love for the guys around me, wanting to serve them, help them succeed, and be reliable for them. Even in losing seasons, that mindset kept me grounded and motivated.

And just as I wrap up, if this documentary were your final word on football, what would you want that word to be?

Chuck “Chico” Kyle: Passion

Matt Waldeck: Belief

Joe Thomas: Servanthood. The idea of putting your team before yourself.

The Object of the Game is available February 4th of Super Bowl week for purchase on Prime Video in the United States.