We love adorable cats. We love compelling video games. And we especially love when the two collide in a mature, story-rich experience that tugs at the heartstrings and reminds us just how deeply our feline friends love us (with spellbinding emotional results).

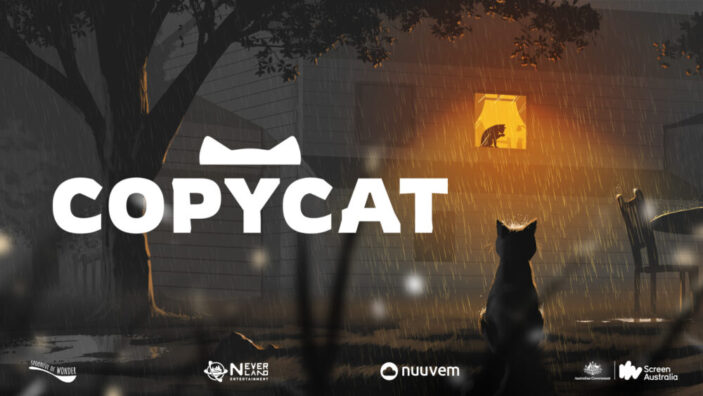

Developed with support from Screen Australia, Copycat is the debut title of developer Spoonful of Wonder, helmed by writer Samantha Cable and director Kostia Liakhov. A narrative-driven video game that explores the highs and lows of family, home and abandonment for both human and kitty-kind, Copycat commands interactive storytelling that lets players explore complex heartfelt themes of rejection, belonging and the true meaning of home.

Released for Steam on both PC & Mac back in September 2024, Copycat is poised to soon release its cuddly paws on PlayStation 5 & Xbox Series X/S. Ahead of its PS5/Xbox release, we got the chance to speak to writer, head of narrative and founder of Spoonful of Wonder, Samantha Cable, on the many wonderful elements that make the game tick.

What inspired the concept of Copycat, and how did you translate that idea into a full-fledged game?

Samantha Cable (SC): Copycat uses the medium of a narrative-led video game to explore the deep love we have for our pets. This special bond we share with our cats (and dogs) is unlike any other relationship. Pets love us on good days and bad. Through the fun times and the tough times. Cats, in particular, have played a big part in my life. But the systemic issue of pet abandonment weighs heavily on my heart.

As the cost of living rises and more people surrender their pets, animal shelters are at capacity. Therefore, I was inspired to write a script that demonstrates the complex and nuanced world of cat ownership. Copycat is about a pet who learns to deal with abandonment, and a human forced to surrender. Together, two souls go on a journey to discover the meaning of family and home. Cats were the perfect vessel to tell this story. I wanted players to walk in the paws of their newly adopted cat and experience the fear of adjusting to a new home. All these themes came together to create our very first game, ‘Copycat’.

Why do you believe sadness is an effective tool for game developers? Can you share specific moments in Copycat where this was intentionally used?

SC: Sadness and melancholy have always been an important part of the human experience. Even in ancient Greek times, we had tragedy to balance out comedy. Sadness aims to move audiences emotionally. For games in particular, sadness and catharsis can provide depth. But they don’t always have to be negative experiences. For example, we can become emotional when we see our protagonist achieve something they never could do before. We can be proud of them. We can feel heartfelt or heartbroken. Without the sadness, the highs are not as profound and magnificent.

It is a real balancing act for game developers. A specific example in Copycat occurs at the Act 2 turning point. We needed an emotional beat that would bind the player with Dawn (the cat protagonist) and experience what it really felt like to be left behind. I used sadness as a tool to pivot into Act 3 and give players the opportunity to reflect on the ethics of pet ownership. This tool meant we were able to carry the emotional throughline of the story and keep players engaged.

Can you walk us through the process of crafting a particularly emotional scene in Copycat? What elements contributed most to its impact?

SC: There are many emotional scenes in Copycat. Some felt fulfilled, and others felt euphoric. Some felt empty, and others felt sentimental. Each scene was crafted with care to make them emotionally resonate with the player. Each moment started with a strong narrative and theme, but there are many other tools developers can use when creating emotional scenes. Let’s explore the directorial tools first. Directors can use colour theory to help with the mood of the scene. In Copycat, cool colours such as blues and greys relate to the feelings of abandonment and homelessness.

This is compared to earlier scenes in the game that are flooded with warm reds and oranges to symbolise safety and love. The camera is another great directorial tool. When we want our player to feel small and overwhelmed, we position the camera further away from the protagonist. Or in particularly intimate scenes, we even swap the camera to a character’s POV. This really helps the player be in the shoes (or paws) of our protagonist.

Music is another great tool for developers when crafting emotional scenes. We have been conditioned as humans to associate different feelings with different instruments. So it’s important to be intentional with instrument selection. We can also play around with leitmotifs and assign different melodies to different characters. It gives the player a certain feeling. So when we revisit this melody later, we can recall this feeling. In our experience, narrative, direction and music work in harmony to create emotional scenes.

In your opinion, why do sad moments linger long after the console has been switched off? What do you hope players take away from these experiences?

SC: Games have the power to touch players deeply. As a result, sad moments linger. The first reason (and one of the most powerful) is because the player has physically experienced the sad moment. The interactive nature of video games goes beyond classic storytelling since our player isn’t just a passive observer (like in theatre, film and television). The player IS the character, meaning it’s them who make the tough choices. It’s them who win and lose. It’s them who end up with their heart broken. None of the existing mediums have such power, making gaming an incredible vessel for our catharsis-charged narratives.

Secondly, sad moments stay with us because we have time to reflect on them. Most games are designed as a longer experience. In the indie world, the players usually expect 6-10 hours of a narrative for smaller projects, while in AAA titles it may take anywhere between 30 and 50 hours to reach the credits. Some games take as long as 300 hours to complete. Because of the duration, players have more time to build a relationship with their characters, the narrative and the world. It’s also the time in between the play sessions that players have to reflect on the sad moments they have just been through. Ultimately, players will also be left with a renewed sense of mental clarity and are free to ponder the story’s deeper meaning.

How do games create a safe space for players to process complex themes like grief and loss?

SC: Catharsis acts as a safety valve, allowing the discharge of pent-up emotions like stress, anger, and sadness. It provides a healthy outlet for audience expression and a safe space to process complex themes like grief and loss. Compared to film or theatre, games give players unique flexibility and freedom of choice—you are often free to explore themes at your own pace.

This makes it more accessible for different players and allows them to pace themselves when going through difficult topics. In many cases, players can step back and do a side activity in the game before they’re ready to embark on a new chapter of the main narrative. Most games, just like books, are also meant to be experienced in multiple sessions by design.

What practical tips would you offer to aspiring writers and developers looking to incorporate catharsis into their games?

SC: Take care of your player and be aware of their limits. Gaming is a relatively new storytelling medium. As much as there are many incredible examples of beautiful and touching cathartic stories available, gaming is still widely associated with ‘fun’, ‘action’ and ‘conquering’. For this reason, our players may have different limits when it comes to heavy narrative, and we need to respect it. We need to take care of the player and understand that sometimes they are there to just relax after a long day and be a cat without having their heart broken.

This also extends to how we position our story. It’s important to not mislead the players and ensure they know what experience they’re getting into. Always consider trigger warnings and craft your game descriptions and marketing materials accordingly to avoid false expectations.

Finally, we suggest aspiring developers should focus on the redeeming quality of the game. At the end of the day, because of the interactive nature of games, they are still heavily reliant on the player winning. For example, defeating the final boss, completing the hero’s journey, or having a closure in another way. If our player feels like they have ‘lost’ the game, it may leave them with a bitter aftertaste and may potentially reflect on the overall reception of the game.

We did the best job we could with Copycat, but in reflection, there are many things we would do to improve. Copycat is far from perfect.

Do you have a personal connection to the themes explored in Copycat? How has that influenced your storytelling?

SC: What a lovely question! Since COVID, Kostia and I have been working remotely, floating between places while working on our game. The experience is very liberating, sometimes lonely, however, we recognise our definition of belonging and home is vastly different from most. Growing up, my family moved houses multiple times between New Zealand and Australia; so it was as if I was living in the in-between, never really belonging to either place.

On the other hand, Kostia has a different relationship with the theme. Kostia can’t return home due to the war in Ukraine. His parents are displaced and haven’t been back to their town in almost two years. We both have a nuanced relationship with the meaning of home and belonging. Therefore, it makes sense that we were drawn to it as a theme.

We want to remind players that home is not certain or a guarantee. Home is not always about things, places, or people. This is because not all of those three things are always possible. Instead, home is a sacred space that evolves and shifts over time. Home can be broken and mended. Home can be abandoned and found. But most importantly, home is the place where you are needed most. These themes of belonging mean a great deal to us, and we wanted to give players an opportunity and quiet space to reflect on it for themselves.

What are some of your favourite emotional moments in other games that have influenced your work on Copycat?

SC: Over the last few years, I had a chance to enjoy dozens of incredible narrative-driven games that made me laugh, cry, think and reflect. Many of them shaped me as a narrative designer. If I were to select a few, I would probably shout the following masterpieces:

- Life is Strange (Don’t Nod, 2015), for its beautiful storytelling and ultimate heartbreak with an impossible choice to make. The character building, music, and plot are a masterclass in storytelling, in my opinion.

- Brothers: A Tale of Two Sons (Starbreeze Studios, 2013) for how they utilised the user experience and the control scheme of the game to deliver the cathartic experience in a new and unexpected way.

- Florence (Mountains, 2018) for how they were able to tell the story and express characters’ feelings with very simple mechanics, relying on visual metaphors, nostalgia and pacing.

Copycat will launch on PlayStation 5 and Xbox Series X|S on May 29, 2025. It is currently available for PC and Mac via Steam.