It’s hard to classify Shaeden Berry’s novels into any one genre. On the one hand, both her latest novel, At Cafe 64 and her debut, Down the Rabbit Hole revolve around a crime. But on the other, Berry’s writing puts its focus so far away from the traditional ‘solving of a case format’ that it could almost be said her novels are more about what happens after the traditional crime book is closed. Perhaps this is what makes her writing so compelling; her focus on the impact of a crime, long after the detectives have said ‘case closed.’

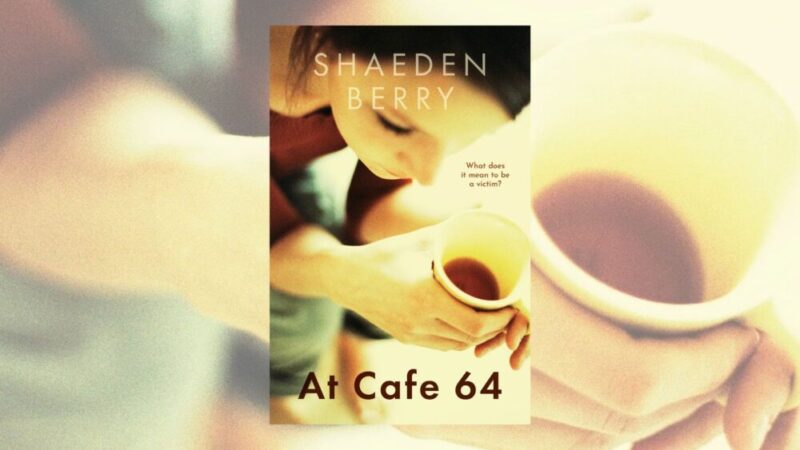

In fact, her most recent book, At Cafe 64, is about precisely this – the long term effects of a violent crime, and about the ways in which those whose lives were altered by a traumatic event approach the idea of ‘victimhood.’ Almost two years prior to the opening of the novel, Justin Kowalski deliberately drove his car through the front window of Cafe 64, killing three people and injuring many more. But as our three protagonists each navigate their feelings about the anniversary, they ask themselves – and the reader – to think about the question of victimhood. Who gets to be a victim in this scenario? And how much say do they have in the matter?

First, we meet Emily – struggling with feelings of guilt and shame, and hiding that she is the killer’s sister, all the while waiting for the real victims of the cafe tragedy to out her as an imposter or find out her secrets. Then, we meet Flo, who missed being caught up in the accident by a matter of mere minutes. Everyone around Flo thinks she’s repressing her true feelings about what she saw, but she didn’t really see anything – or did she? Finally, we meet Maddie, whose life has been ripped apart by the accident, which killed her fiancée. Her anger has left her jobless, friendless and looking for someone to blame. But, while she may have the most traditional claim of them all to belong at the support groups and in the Facebook pages, Maddie is hiding in plain sight, claiming to be making a true crime podcast.

The brilliance of this novel is that it explores the universal impulse to relate the biggest, and scariest things in our world back to our own experience. When local news breaks, how many of us have never thought about their own proximity to the tragedy, our own connections to the places and people involved?

Emily – who has changed her name, and become a shadow of her former self, desperate not to draw attention to herself – lurks on the edge of social media communities dedicated to victims of the Cafe 64 tragedy and watches as people call one another out for not being ‘real victims’ – or for being ‘disgusting leeches’ feeding off the drama of other people’s suffering. All the while, she wonders what they would say if they knew she was among them, despite the fact that her brother died that day too. Emily’s story raises several philosophical and moral questions – does Justin’s culpability erase the rights of his mother and sister to mourn him? And are there evil people, or only those who are driven to evil acts? (Just as a side note, I don’t think it is a coincidence that Justin shares his surname with Stanley Kowalski, the famous violent husband of Tenessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire.)

Each of the three point of view characters embodies a different response to what has happened, with Emily’s reaction being one of shame, and a need to control the narrative and protect her family – what is left of it. Flo’s experience is that of the ‘near miss’, and she grapples with the knowledge that if she’d changed one tiny thing about her day, she might have been killed too. Her insistence that she is fine, and her constant talking to fill the silences around her, indicate that she is anything but okay. Maddie, on the other hand, refuses to be a victim. Her grief manifests as anger; hers is a destructive force within the novel, though at first, it is only her own life that she wreaks havoc on. But when the three women meet at a support group, and Emily decides that the only way to stop Maddie’s podcast finding out too much is to sabotage it from the inside, each young woman is forced to admit the things they won’t even say aloud to themselves.

Despite all of this, friendship, community and the support we get from those around us is an important theme of this book. The focus on thinking through big ethical questions about who gets to be affected by traumatic events might place the novel firmly in a literary fiction category; so too might the beautiful, stripped back prose which does not rely too heavily on melodrama. Yet the placing of a quest for self acceptance or the gentle exploration of how good friendships can be formed out of bad times might also make this book ideal for the reader of contemporary fiction.

While the subject matter is dark, this is a hopeful book and one that is less likely to have you wallowing in a pit of despair than it is to send you off to call that friend you haven’t seen in a while. At Cafe 64 is deeply hopeful, a book more about healing than about grief, and it was a true delight to read.

Pick this one up if the idea of a Sally Hepworth novel crossed with Dirt Town by Hayley Scrivenor appeals to you. And if you don’t know what that means? Maybe pick it up anyway and find out.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

FOUR STARS (OUT OF FIVE)

Shaeden Berry’s At Cafe 64 is out now through Echo Publishing. Grab yourself a copy from your local bookstore HERE.