Kathleen Jennings‘ debut novel, Flyaway was a quiet achiever of a novel– it wasn’t the title on everyone’s lips, but those who knew it, raved about it. Published in 2020, it was a finalist for the 2021 World Fantasy Awards and the 2020 Crawford Award, as well as one of NPR’s picks of 2020. Kathleen is also an illustrator and a poet, and her work bears the hallmarks of these crafts in the lyrical prose and eye for beauty.

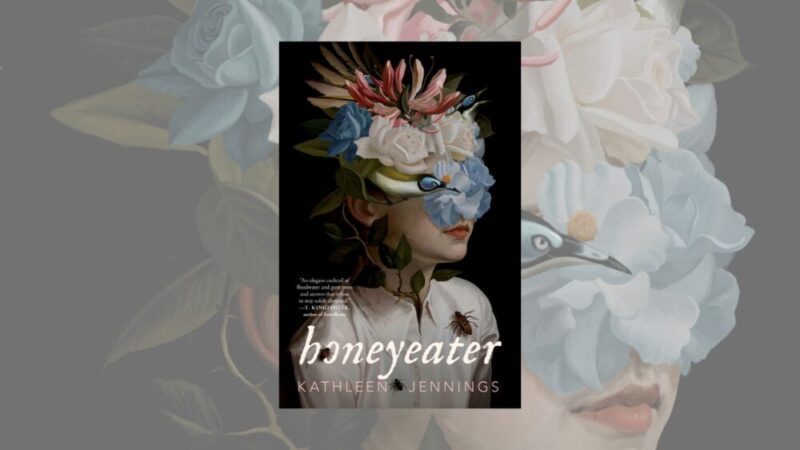

Honeyeater, her second novel, was published in September 2025. The story of a Queensland town called Bellworth, founded by a number of ‘influential’ families on the banks of a river prone to flooding, the novel explores the line between fantasy and fallacy when it comes to the making of local legends.

Wren siblings, Charlie and Cara, are called to the home of their aunt to clear out her belongings after her death. Charlie is beleaguered by misfortune — after an attack at the river as a child, he has an uncomfortable ability to be able to find things washed up by the tide. Unfortunately, some of these things are the bodies of missing people, and people around Charlie have a habit of going missing. As a result, Charlie has become somewhat solitary, and tries to shrink himself to avoid notice of the police. Conversely, his older sister Cara is the golden sibling, beloved by friends and neighbours, and in the running for local council. She doesn’t have much in the way of time for clearing out the house, but she has reasons for wanting Charlie to do things properly, and quickly.

The arrival of Grace makes things complicated, however. Human, possibly, but increasingly not, Grace seems to be a collection of memories given the form of a young woman, made of roots, branches, and flowers. She believes that she once was someone, but doesn’t know who. She knows only that as soon as she became conscious, she was drawn to the Wrens. Charlie takes her in, and wants to help her find out who – or what – she is. But, Cara is less willing to trust someone who may be a kind of ghost. As strange things begin to happen and eerie presences converge on the property, the sense of imminent danger grows. Meanwhile, a young neighbour known only as the Taxi Driver’s Daughter watches on.

Each chapter of this novel is introduced with a short anecdote by a member of the neighbourhood, reminiscing about the strange goings on in the street and its surrounds. The recollections are sometimes magical, and sometimes lean more towards a nightmare, showing the ways in which gossip and superstition can build into the kinds of local legends which endure through generations.

Jennings is clever in the way that she builds this sense of neighbourly unease. Everyone knows all the rumours about everyone else, but they are remote and isolated, each obeying the ‘rules’ and allowing the status quo to continue. Like in so many instances throughout Australian history, Bellworth was founded on the banks of a river that would flood many times throughout the lifetime of the place. The hubris of the early members of these prominent families leading them to choose the prestige of riverside views over the practicality of seeking safer ground. I thought that the subtle corrections made in the narrative each time a character referred to these settlers, as if there was no history of the place before them, was incredibly well done.

The river and the landscape are not only the central thread of the book, but also seem to have a kind of living presence in the book too, with Charlie and Grace always aware of the river, and its potential. The looming sense of danger from the natural landscape and a fear of the unknown is quintessential Australian gothic, without delving too far into horror. There is definite menace, and some low level violence, but nothing that I would glass as gore.

There was something a little untethered about the story, however. And I could not work out where we were in time. The tone had a sense of the historical about it, but the majority of it happened within the space of one house and backyard, and so outside events could not filter in. There were cars, but no mention of makes or models, and when Charlie and Grace made their way to the library to search for more answers, it did seem possible that the book was set later than I had assumed. This unreality also sometimes extended to the more magical aspects of the book, with the use of poetic description obscuring whether some of the things were metaphors or literal descriptions; for example, I could not picture exactly how human Grace was supposed to look, sometimes supposing her to just appear as a heavily tattooed woman and sometimes wondering if she was more like a woman shaped kokedama. Most of the time, however, this did not impact the storytelling.

The book has a tone reminiscent of Jock Serong’s Cherrywood, perhaps also due to Honeyeater‘s focus on local history and legacy, as well as its use of a river motif. If you loved that book, I suspect you will love this one too.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

FOUR STARS (OUT OF FIVE)

Kathleen Jenning’s Honeyeater is out now through Picador Australia. Grab yourself a copy from your local bookstore HERE.